When Kyla awoke she expected to see the interior of Zammie’s house back in the suburbs of Long Beach, California. Instead, she was still outside and she could see the pale blue and orange glow of sunset commencing in the western sky. Surprisingly she was lying by a cobblestone road on the outskirts of a small town.

Her clothes had changed. Instead of having on a skirt and sweater she now had on a green and white crisscross patterned dress with a brown belt around her waist. Her single pony tail had turned into two braided pig tails.

She saw Zammie still sleeping in the grass a few yards away from her. There were several brick houses nearby, and she could see apartment buildings and storefronts further down the road in a direction that appeared to lead towards the center of the town. In the other direction was an old synagogue made of brown and gray stones with several arched windows on the sides. A large Star of David was stationed within a circular window pane just above the front doors.

“Where are we now?” Kyla said to herself.

Kyla heard the sound of children giggling behind her, and when she turned to look she saw two young girls standing close to Zammie. Zammie was still asleep in the grass and the two girls were tentatively stepping closer to him. They were curious why a young boy would be sleeping by the street in the late afternoon.

She stood up and walked towards them. The two girls smiled back at her. “Hello,” they both said.

Both girls were wearing clothing similar to Kyla’s. The younger girl had light brown hair and looked to be about nine years old, and the older, darker-haired girl was probably Kyla’s age.

Zammie lifted his head and looked around.

“What’s going on?” he asked. “Where are we?

“They speak German!” they younger girl said to the older.

“Huh? Hello,” said Zammie. He immediately stood up and began straightening his appearance when he realized there were girls around. He paused for a second when he noticed his clothes had changed. He was now wearing green shorts with beige wool socks that were rolled up close to his knees. He tugged on the suspenders that went over his shoulders and the light blue button-down shirt he was wearing.

“Shorts again?” he asked. “Don’t boys wear ever pants in Europe when it gets cold?”

“We’re still in Europe?” asked Kyla.

“You’re in Germany,” said the older girl. “This is the village of Schermbeck.”

“What’s the date?” asked Zammie.

“The ninth,” said the girl.

“Of November?”

“Yes.”

“Nineteen thirty-eight?”

“Of course,” said the girl. “My name is Marga. This is my little sister, Susan.”

“Hi, Marga. My name is Zammie, and this is my cousin Kyla.”

“We thought you were Japanese,” said Susan.

“Japanese?” Zammie smiled. “We don’t even look Japanese.”

“So what happened to Herschel?” Kyla asked Zammie.

“I don’t know?”

“Who is Herschel?” asked Marga.

Before Zammie could answer they were interrupted by a woman calling the two sisters.

“Marga! Susie! Back home now, please!”

Marga exhaled. “It’s mother. We have to go home for supper.”

“Oh.” Zammie immediately became aware of how hungry he was again. He was always hungry when he woke up on these trips. Actually, he was usually hungry when he woke up period.

“You want to have supper with us?” asked Marga. “My parents won’t mind.”

Zammie and Kyla exchanged looks. “We’d love to,” said Zammie.

The sisters led the two cousins down the cobblestone street past several other seemingly empty houses to where their mother was waiting for them. The entire neighborhood had an eerie empty feeling to it. There were plenty of houses and shops along the streets, but there weren’t many people around.

The girls’ house was three stories tall and made of reddish-brown bricks. Large windows with white painted panes and lace curtains made it look not too dissimilar from houses in the eastern part of the United States.

“Zammie.” Kyla pulled her cousin to the side as they walked. “So we fell asleep in France and woke up in Germany? And it’s how many days later?”

“Two days. It was the seventh when we were in the taxi.”

“That’s weird. This has never happened before. Usually when we see the Arjuna and go to sleep we wake up back home.”

“I know. I don’t get it.”

Marga was the first to arrive at the house. “Mother. We invited guests for supper.”

Marga’s mother wore a white blouse with a dark red skirt. She had thick brown hair with the sides pinned back similar to the way Susan wore her hair.

“Guests? These children?”

“Hello, ma’am. My name is Zamuel Pineda and this is my cousin Kyla Reynoso.”

Marga’s mother didn’t know what to make of the two cousins at first. There weren’t many Asians in this part of Germany.

“Nice to meet you both. My name is Esther Silbermann. And I don’t believe I’ve seen you two around before? You’re not from Schermbeck, are you?

“We’re tourists,” said Zammie.

“Tourists? In Schermbeck? Ha! You need a new travel agent. Where are your parents?”

“In America.”

“Oh! And you’re here on your own?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Esther couldn’t believe it.

“Esther, get the children inside,” said a man’s voice from the house.

“We’ve picked up two strays, Frederick,” said Esther.

A man with a thin black beard walked out on the porch next to her. He was wearing black pants and a white shirt with suspenders similar to Zammie’s.

“Who?” The man eyed the two cousins. “You speak German?”

“Yes, sir,” said Zammie.

“They’re traveling abroad,” said Esther. “Their parents are in America.”

“America?” said the man. “Then bring them in as well. It won’t be safe out here tonight.”

Marga clapped her hands when her parents agreed to let the cousins stay for supper. The two sisters appeared to be happy, but Kyla and Zammie noticed the worry that lined the faces of their parents.

The inside of the house was a blend of traditional German and Jewish influence. The wooden fixtures, clocks, and architecture were of classic German design and engineering. There was also a silver decorative case containing a mezuzah attached to the front doorframe (the case held a piece of parchment upon which select verses from the Torah were written). A quilted tapestry hung on the wall with twelve squares representing the twelve original tribes of Israel, and Zammie noticed a couple small wooden statues on the book shelves that looked like dancing Rabbis.

The inside of the house was a blend of traditional German and Jewish influence. The wooden fixtures, clocks, and architecture were of classic German design and engineering. There was also a silver decorative case containing a mezuzah attached to the front doorframe (the case held a piece of parchment upon which select verses from the Torah were written). A quilted tapestry hung on the wall with twelve squares representing the twelve original tribes of Israel, and Zammie noticed a couple small wooden statues on the book shelves that looked like dancing Rabbis.

|

| A mezuzah case |

The savory smells of boiling vegetables, meat stock, and baked bread greeted the children when they entered the house. It was very warm inside. The family had a black potbelly stove called a kachelöfen that had a fire going. An older woman with gray hair wearing an olive-colored dress was setting the food out on the table. Esther walked to the kitchen and began helping the older woman.

Kyla spotted a bright yellow canary in a large cage in the living room. Her eyes lit up.

“Ahh,” she said. “You have a canary!”

The older woman smiled. “Yes, that is Little David. He is Grandpa’s most prized possession. More highly prized than even me.”

“I heard that,” said the old man in the living room. He had thin, silver hair and was sitting on a small sofa listening to the news reports on the radio.

“I’m sure you did,” said Grandma. She winked at Kyla.

“Don’t let her lie to you,” the old man said to Kyla. “She knows she’s my only true joy. But that bird is a close second.”

Kyla loved little birds. She whistled for David, trying to get him to do the same. His little black eyes and golden head darted around trying to comprehend what exactly this young girl wanted from him.

Marga’s father walked into the living room where Grandpa was listening to the radio. “Anything?”

Grandpa continued listening for a few seconds. “He’s dead,” he said finally. “Vom Rath is dead.”

Kyla noticed that it became very quiet in the house all of a sudden. The only noise was the tinny sound of the radio news announcer. She felt a little bit uncomfortable as if she and Zammie had interrupted a private family matter.

“Turn off the radio, Grandpa. Supper is ready. Come eat,” said Esther.

Marga and Susan sat across from each other at the table. Zammie and Kyla sat next to Marga. Esther and Marga’s father Frederick sat at opposite ends of the table and Grandpa and Grandma sat next to Susan. Frederick gave a brief blessing, and the plates began to be passed around.

“What is it like in America, Zammie?” asked Marga.

“It’s nice,” was all he could muster. He was distracted by the sights and smells of the steaming vegetables and meat dishes going around the table.

“You’re from America?” asked Grandpa. “I’m sure it’s nice. You don’t have these problems over there.”

“What problems, sir?” asked Zammie.

“It’s about time someone stood up to these goons,” said Frederick. “Herschel should be considered a hero.”

“A hero?” said Grandpa nearly dropping his fork. “Killing a man in cold blood makes no one a hero.”

“Herschel?” asked Zammie.

“You think we should just stand back and take this treatment, father?” asked Frederick, ignoring Zammie’s question. “They boycott our businesses. They take away our citizenship. At what point do we say ‘enough’? Something must be done. We are Germans. No different than them!”

“Of course, Frederick,” said Grandpa, “but ‘doing something’ doesn’t mean killing a man. You’ll see this will give them free license.” Grandpa glanced at the front of the house. “As soon as we’re done eating we need to close the shutters. And don’t answer the door tonight.”

“What for?” asked Frederick. “You want to go into hiding? You think that will save us?”

“Enough. No yelling in front of the guests, please,” said Grandma.

“We’re not yelling, mother,” said Frederick.

Zammie was enjoying the hearty kishka sausages and potatoes he was given when he decided to speak up. “Excuse me. So that man that Herschel shot died?”

“Yes,” said Frederick. “Just a few hours ago, they said.”

“And now you watch what the Nazis will do,” said Grandpa. “Any excuse to tighten their grip on the Jews.”

“What happened to Herschel?” asked Kyla.

“Arrested of course,” said Grandpa. “I’m sure they will give him a plebian trial and then execute him with as much pageantry as possible. That’s the Nazi way. All style. No soul.”

“Poor Herschel.” Kyla looked at Zammie with her sad, brown eyes.

“I guess he felt he had no other options,” said Zammie.

“There’s always another option,” said Grandpa.

“That’s enough talk about Herschel,” said Esther. “May we change the subject, please?”

Everyone did their best not to bring up the subject of Herschel or the death of Ernst vom Rath while they ate, but the questions and tension still hung in the air. Had Herschel really felt that the murder of a German Embassy worker was the only way to draw attention to the plight of his parents and the other Polish Jews? What sort of reaction would the Nazi government in Berlin authorize in response? They would never know the real answer to the first question, but they would soon learn the answer to the second.

After dinner, Esther rolled out two floor mats upstairs in the girls’ room. Marga and Susan had offered to sleep on the floor and allow the cousins use of their twin beds, but the cousins refused. They were used to sleeping on floor mats and were more than grateful for the opportunity to sleep indoors on this cold night.

The girls had one of the rooms in the front of the house on the second floor. It was a small room filled with pretty dolls and hand-crafted wooden furniture. Two large windows in the room overlooked the cobblestone street outside. The street led towards the center of town. Houses, churches, and shopping centers had been built up around a well-structured grid of streets that were wider than some of the roads in Paris. The buildings were better spaced out as well, but this was no large city.

“Nearly seven thousand people live in Schermbeck,” Marga told Kyla. The low light of an oil lamp gave a ruddy glow to her face. “There used to be many more Jewish families around here, but many of them have moved away. I think there are only a few families still here. Not even enough to fill up the synagogue.”

“Is that why there’s so many empty houses around here?” asked Zammie.

“Yes. Both of our neighbors have moved away.”

“Mister Behr hasn’t left yet,” said Susan. She had been listening intently as the older children spoke.

“Yes,” said Marga. “Mister Behr lives across the street by himself. He’s too old to leave.”

“Why do they leave?” asked Kyla. “And where do they go?”

“I don’t know why they leave,” answered Marga. “My mother says it’s because they don’t get along with other people, but my father says it’s because of the Nazis. I’m not sure where they all go. Some go to France. Some to Holland.”

“I heard your Grandfather talking about the Nazis.” Zammie sat up straight. “Is Hitler in power now?”

“You don't know?” asked Marga. “He’s our Chancellor. But some people say he won’t be in power for long. They think he’s a clown, and that the people will stop listening to him soon.”

“Oh, no.” For the first time Zammie began to feel real fear for this family.

There was a knock at the door. Esther poked her head inside.

“Lights out,” she said. “Time to sleep.”

“Yes, mother,” said her two daughters.

Marga turned off the lamp and the children bedded down for the evening. It was just past nine o’clock. Zammie couldn’t sleep. His mind was still wondering why they had showed up here. He wondered if he would see Herschel again. Then he began to wonder if he and Kyla could change history. What if they could rescue Herschel from the Nazis? He wondered if he could do anything that might change the current path that was leading to World War II. Unlikely, he thought. What could two little kids do against these growing international war machines?

At just past ten o’clock Kyla heard the patter of bare feet flitting past her on the wooden floor near her head. She looked up and saw Marga looking out the window onto the streets below.

“What is it?” asked Kyla. She could now hear noises coming from outside; the sounds of voices in the streets.

“I thought I heard a crash,” said Marga. “There are people out here.”

“Who is it?” asked Susan.

Both Susan and Zammie were now awake as well. All three children rushed over to join Marga at the window. It was still dark in their room, but their faces were illuminated through the thin plate glass by the glow of burning torches being held by the people outside. Moving up the road towards the house they saw volunteer firemen dressed in heavy coats and helmets. There was smoke rising from a couple buildings a few blocks away from them.

“There’s a fire!” said Zammie. “And there’s another one!”

Crowds of people were now filling the streets. Zammie spotted several soldiers going door-to-door holding large, growling German Shepherds on leashes. Some of the villagers were throwing rocks and bricks through the windows of every building they passed. Why didn’t the police stop them? thought Zammie. Other people were tossing lit torches through the smashed windows of some of the storefronts.

Kyla saw a gang of men break down the door of one of the houses and barge inside. A few moments later she saw them dragging an older man and woman out of the house and throwing them in the street. The woman was crying hysterically and the old man was trying to calm her down. They were both in their sleeping garments.

Then the children watched as a gang of young men dressed in brown shirts and pants approached the synagogue just a few doors away and began throwing bricks through all the windows.

“What are they doing?” Marga gasped.

|

| A synagogue burns on Kristallnacht |

Other villagers threw torches into the synagogue and within seconds a large fire began to swell inside the sanctuary. Soon the flames were burning through the wooden roof.

“Who are those people?” asked Zammie.

“I don’t know,” said Marga. “I don’t recognize any of them.”

Marga noticed a few of the men who were wearing brown military shirts began walking towards her house. Nearly everyone in the street was carrying a torch in one hand and a large rock in the other.

“They’re coming this way!” said Marga.

“Are they gonna hurt us?” asked Susan. Her eyes were filled with terror.

Marga could hear her father and Grandpa talking downstairs.

“Let’s go downstairs. Follow me!” she said.

Marga led the other children out of her room and down the hardwood steps. When the children arrived downstairs they found Frederick and Esther and the Grandparents all looking out of the windows.

“Stay back!” said Esther when she saw Marga.

“What are they doing, mother? Why are they burning the synagogue?” asked Marga.

At that moment a brick flew through the kitchen window with a loud crash and landed on the floor. Susan began crying and ran to her mother.

“Everyone, this way!” said Frederick. He herded his parents and the children towards a small room in the back of the house on the first floor just as another brick flew through another window and landed on the floor next to Zammie’s feet. Chipped shrapnel from the brick and glass shot up and stung Zammie’s shins on impact.

“Watch out, Zammie! Are you okay?” asked Kyla.

|

| A synagogue burns from within. |

“I’m fine. Follow Mister Silbermann!”

Everyone went into the small room. Frederick kept the door open a little to make sure no torches were thrown inside the house. Grandma and Grandpa held each other close. Esther held one daughter in each of her arms. All three of them had tears streaming down their faces.

After a few minutes had passed and nearly two dozen bricks had been thrown through virtually every window on the front of the house, they heard the front door being knocked down. Several men in brown military uniforms entered the house and began destroying the furniture. They smashed the chairs and tables. They used clubs and axes to break the dishes and rip down the wall decorations, cursing and laughing as they went about their destructive work. The bookshelves were toppled over and the books were picked up and ripped apart. The mezuzah case was torn from the door frame and tossed out into the yard. The tapestries were yanked from the walls and thrown out of the broken windows where they snagged and tore on the shards of glass.

Frederick couldn’t take it any longer. He opened the door and approached the uniformed men.

“Frederick!” yelled Esther.

“Where are you going?” yelled Grandpa. “They will kill you!”

Frederick ignored the pleas of his family.

“What are doing to my home?” he asked the first Nazi officer her saw.

“This is no longer your home,” said the officer. “All Jewish houses in this area have been seized by your government.”

“Siezed?” asked a shocked Frederick. “For what purpose?”

Frederick didn’t recognize the man. In a village of only 7000 people it was rare when an unrecognized face would appear. Frederick wondered if these men were actually from Schermbeck. The officer called over two policemen who were standing near the front door.

“Arrest this Jew,” he told them. “He is trespassing.”

Frederick couldn’t believe his ears. The policemen quickly grabbed Frederick and began to drag him towards the door when Esther came running up towards them yelling.

“Let him go! Please!” She ran to the Nazi official and handed him a small medal with a black and white ribbon attached to it. “My husband was in the army! He fought for Germany against the French! You can’t force him out of his own home!”

The Nazi official took the medal and looked at it. It was an Iron Cross 2nd class. The policemen had stopped and were waiting on the verdict from the Nazi officer. The medal had certainly captured the officer’s attention.

“You fought in The War?” asked the officer.

Frederick nodded.

“Where?”

“Western Front. Verdun.”

“Verdun? Under whose leadership?”

“General Von Lochow. Third army corps.”

The officer thought for another second. “Not a pretty sight, Verdun."

Esther held her breath.

"Let him go,” the officer finally said.

The policemen let go of Frederick. Esther ran over and hugged her husband.

“I can do nothing for your house,” said the officer. “So I advise you to take your family and leave. I cannot guarantee your safety if you stay.”

|

| Hitler Youth, 1938 |

Several young boys, probably in their early teens, were allowed inside the house and they began smashing any of the unbroken furnishings they could find with black clubs they had been given. They relished the opportunity to destroy whatever was available. Even if something was already smashed the boys would hit it again just to make sure.

Frederick and Esther ran back to the room and ushered everyone out the back door of the house. They stepped out into the cold night air where they saw two other Jewish families huddled together. They were watching the synagogue burning to a black crisp. The gray stones that made up the walls would soon be the only remnants left of the structure that had been built nearly one hundred years earlier.

“Where do we go?” asked Esther.

“These people are animals,” said Grandpa. “Maybe Herschel made the right decision after all.”

“The children don’t even have clothes, Frederick,” said Esther. “They’ll freeze out here.”

None of the children had much clothing on. The girls were all wearing night gowns and Zammie had on his green shorts and his white shirt.

“We can go to the hospital. They’ll give us shelter for the night there,” said Frederick.

“The Catholic hospital?” asked Grandpa. “It’s on the other side of the woods!”

“Exactly. It’s away from here.”

The temperature continued to drop, and they needed to find shelter soon. Frederick led both his family and the other two families they met in the street through a dark wooded area. The moon was just a waning sliver in the sky, and it was being covered by plumes of dark smoke. They walked for nearly two miles until their cheeks, noses, and toes felt like they were frozen through. Kyla and Zammie held each other’s hand as they walked, and they stayed close to Marga and Susan.

Even after walking for more than a mile they could still see the faint light from the burning buildings back in the village. They could also see the light of fires in other villages in the distance.

After picking their way through the trees for nearly two hours they stumbled upon the Catholic hospital. It was built in a clearing in the woods and helped serve the medical and charity needs of several of the surrounding towns. It was a large building made of brick and limestone with a series of concrete steps that led up to a wide, well-lit porch.

Frederick led his weary band up the steps where one of the nuns had already spotted them and greeted them at the front door. She was an older woman wearing a white habit. Two other nuns also arrived to help her bring the refugees inside the hospital and set them up in one of the rooms.

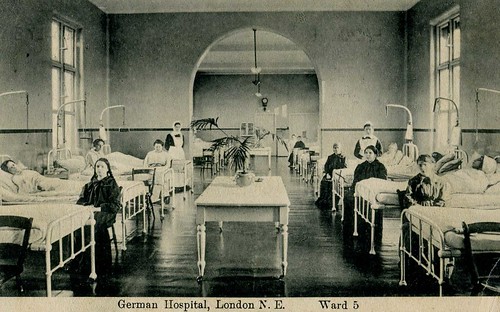

The hospital contained several rooms that each held two long rows of beds. The nuns set the families up in the corner of one of the rooms. They didn’t have any beds to offer, but they did have a couple cots and chairs and they gave them some hot soup that was basically just a watered-down chicken broth with small dumplings.

Kyla looked around at the hospital beds in the room and wondered how anyone was able to be cured without the modern technology that existed in the hospitals of her time. She saw a young girl in one of the beds with a very pale face who was coughing. A small teddy bear had fallen off the bed and had landed on the concrete floor a few feet away. The young girl, who was probably just six years old, looked longingly at the stuffed animal but she didn’t have the energy to get out of bed and claim it.

Kyla got up and walked over to the teddy bear and picked it up. She handed it to the girl, and the girl took it into her arms. She held it with what little strength she had.

“Tank you mam,” said the girl.

“You’re welcome.”

Kyla smiled and brushed aside some of the girl’s sweat-matted hair from her forehead. She wondered what sickness the girl had, but she didn’t want to ask her. She sat with the girl for a several minutes until the girl fell asleep. Kyla was confused why a place like this, where sick children were being cared for as best they could, could be so close to a place where soldiers and firemen were, at that very moment, destroying the homes of other children. Why the difference in attitude? Who got to decide who would be helped and who would be harmed?

In the other part of the room, Frederick had been talking with the members of the other families who were traveling with them. The men were huddled together on the chairs they had been given while the older women were given the cots on which to lay down.

“I didn’t recognize any of those officials,” said Frederick. “I don’t believe there were from Schermbeck.”

“Of course they weren’t,” said one of the other men. “Those Nazis were from Brünen. And the Nazis from Schermbeck had been sent to Dorsten.”

“What?” gasped Esther. She sat up from the cot. “But why?”

“Because it’s easier to attack people you don’t know personally,” said Frederick.

“So who told them which village to go to?” asked Esther.

“This entire operation had been fully planned,” said the other man. “It had been planned for months.”

“Impossible,” said Grandpa.

“Not impossible, father,” said Frederick. “When will you understand how well-organized these people are?”

“He’s right, sir,” said the other man. “These actions had been in the works for weeks, but they needed an excuse to launch it.”

“And that excuse was Herschel Grynszpan,” said Frederick.

“Exactly,” said the man.

A moment later, one of the nuns entered the room followed by another Nazi official in a brown uniform. This was a different official than the one who was in Frederick’s house before. The official saw the haggard group and walked over towards them. Frederick stood up as the official approached them.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we need you to please return to your homes,” said the official. “You cannot stay in this hospital.”

“Our homes that you destroyed?” asked Frederick. He could feel his emotions beginning to boil.

“We were trying to stop the mobs from demolishing your village, sir.”

“You were what?” Frederick was nearly apoplectic. “That cannot be true! I saw your men break into my house and begin smashing my furniture with my own eyes!”

“I’m sure you are mistaken, sir. But I can promise you we have scattered the hooligans, and it is now safe to return to your homes. Once you have returned home we will need you to make the necessary repairs to your houses as quickly as possible. If you do not leave this hospital promptly I will be forced to have my men escort you out. And I would really hate to do that.”

Frederick was unable to think straight. His heart was pounding. “You swine!” he said. “You lie to my fa—“

The officer backhanded Frederick across his mouth before Frederick could finish his sentence.

“I advise you to control your emotions, sir.” The officer turned around, nodded to the nun, and left the room.

“Father!” Both Marga and Susan ran over to Frederick and hugged him.

The nun approached Frederick. “I am so sorry.”

Frederick felt the welt on his mouth and looked at his hand for signs of blood. “It’s not your fault.”

Over the past three hours, Marga and Susan’s world and their understanding of how it worked had completely changed. When Kyla and Zammie had first met them earlier that afternoon the two sisters were naïve of such conflicts between their national government and the Jewish people. Their parents had hid the bad news reports from them; the boycotts of Jewish businesses, the deportation of Jewish citizens, and the growing restrictions on religious and economic freedom within Germany. Over the past few hours, however, they had seen some of the fruition of that growing plan against the Jews by their own home government.

|

| Things to come: Jews being rounded up in the 1940s. |

Home government.

That was the part that had angered Frederick the most. His parents had immigrated to Germany from Belgium before he was born. Since their immigration they had done their best to assimilate into German society. They learned the language, they celebrated the holidays, they paid their taxes, and they ran their modest furniture shop in a way compliant with all German law. On top of all that they had raised a son who willingly went off to fight in a terrible war in defense of Germany. It was a story that could have been repeated more than a thousand times over amongst the Jewish population of the day. And this was how they were all repaid.

The refugees returned through the woods back to their homes that night. By the time they arrived back in Schermbeck it was near four in the morning.

Frederick led his family inside their house and the two cousins closely followed. They could see very little in the darkness when they walked inside. The electrical lights didn’t work, so Esther lit an oil lamp to provide light. What they could see was shocking.

All of their furniture had been smashed to pieces. All of their dishes had been pulled out of the cupboards and thrown onto the floor. The lace curtains had been ripped down from the hinges. Their prayer books had been tossed into the compost heap outside and mixed in with the rotten vegetables and animal manure. Esther was horrified to see a pair of scissors jabbed into the faces of her daughters in a series of their baby pictures. The toilets had been ripped out from the walls, and even their kachelöfen had been knocked over and smashed. Black coal and ash were spread all over the floor.

Everyone was startled to a halt when they heard Grandma shriek in fright.

“What is it, mother?” asked Frederick.

“Look what they’ve done! Look what they’ve done!” was all she could say.

“What is it?”

Frederick and Grandpa walked over to where Grandma was standing and looked down on the floor. They saw a small, red wet smear mixed in the glass and ash. Partially covered by the leg of a table was Little David, Grandpa’s prized canary. It had been crushed under the weight of a boot. Part of the boot print could still be seen outlined in the ash.

“Davy! No!” said Susan. She began to sob. “Father, who would do that?”

Zammie wondered how much worse the evening could become for this family. Their house had been wrecked, they had no stove to produce heat, and there wasn’t even a chair for Grandma to sit in.

To help keep out the cold wind Frederick and Grandpa began boarding up the windows with some of the loose lumber. Zammie helped with some of the nailing. Kyla would hold up one end of the board while Zammie nailed it into the wall, covering the glassless windows.

The cousins were impressed at the will this family had to continue forging ahead. It was a frightening place to be in for them because there was no legal authority they could rely on for protection or to hear their grievances. The perpetrator of this crime was the government itself – the same institution tasked with protecting its citizens. When the government is working against you, who else can you turn to for justice?

Upstairs, Kyla was helping Marga and Susan clean up their room. They swept the glass and trash into little piles, swept the piles into a tin dustpan, and tossed the refuse into a garbage bin.

“I don’t understand why this happened,” said Marga. “I had no idea they hated us so much.”

|

| Aftermath of Kristallnacht |

Kyla really didn’t know what to say. “What will your family do now?” she asked.

“I don’t know. Try to rebuild I guess.”

“What if those people come back?” asked Susan.

Marga had no answer for her sister. Her eyes began to fill with tears.

By the time the windows were boarded up and most of the broken glass and ash had been swept away the sun had begun to crest above the horizon. Zammie walked out of the house and onto the front porch. The synagogue was still smoldering nearby. It was covered in black soot. All of the wood fixtures had evaporated in flame. The glass Star of David had been smashed down with bricks. The streets were littered with shattered glass, rocks, and pieces of furniture, clothing, and trash.

Why did they do this? thought Zammie. For what crime were they being punished?

He saw the old man that lived across the street walking back to his house. It must have been Mister Behr that the sisters had told him about. The man was wearing a white prayer shawl and he had his tefillin strapped around his head. The head-tefillin are a set of small black leather boxes that contain scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah. Zammie watched as the man looked up at the destroyed synagogue nearby and at all the remnants of his neighbors’ lives that had been strewn about on the street like worthless trash. He raised his hand to God and with tears running down his face asked Him, “Why?”

What became known as “Kristallnacht” (translated literally as "Night of Crystal" but usually referred to as the "Night of Broken Glass") was an outpouring of violent anti-Jewish pogroms that took place throughout Germany on the night of November 9, 1938. Pogroms in general refer to any violent riots against Jews, their person and their property, while being condoned by government officials and law enforcement.

In the days following Kristallnacht, the German leadership announced that the attacks had originated as a spontaneous outburst of public unrest, and that it was in response to the assassination of Ernst vom Rath in Paris by Herschel Grynszpan. The Nazi Party chose to use the assassination as a pretext to launch this night of anti-Jewish attacks. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda, was the chief instigator of the pogrom. At his command, regional Party leaders issued instructions to their local offices, and violence began to erupt in various parts of Germany throughout the night of November 9 and the early morning hours of November 10.

The rioters destroyed more than 260 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many of the synagogues burned throughout the night. Local firefighters had been told to stand down and to only intervene to keep flames from spreading to non-Jewish buildings. According to some estimates, the gangs of Nazi storm troopers had destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish businesses, set fire to more than 900 synagogues, while killing 91 Jews and arresting and deporting roughly 30,000 Jewish men to various concentration camps.

The rioters destroyed more than 260 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many of the synagogues burned throughout the night. Local firefighters had been told to stand down and to only intervene to keep flames from spreading to non-Jewish buildings. According to some estimates, the gangs of Nazi storm troopers had destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish businesses, set fire to more than 900 synagogues, while killing 91 Jews and arresting and deporting roughly 30,000 Jewish men to various concentration camps.

|

| Joseph Goebbels |

Kristallnacht finally provided the Nazi government with an opportunity to completely remove Jews from German public life. At that time, it was the crowning event in a series of anti-Semitic policies initiated when Hitler first took power in 1933. Within a week of Kristallnacht, the Nazis had declared that the ruined Jewish businesses could not be reopened unless they were to be managed by non-Jews. By mid-November, Jewish children were barred from attending school, and shortly afterwards the Nazis issued the "Decree on Eliminating the Jews from German Economic Life." This decree prohibited Jews from selling goods or services anywhere, from engaging in crafts work, and from serving as the managers of businesses.

To add insult to injury, the Nazis determined that the Jews should be held liable for the damages caused during Kristallnacht. "The Decree on the Penalty Payment by Jews Who Are German Subjects" also imposed a one-billion mark fine on the Jewish community, supposedly an indemnity for the death of vom Rath.

Zammie noticed a young boy carefully riding a bicycle through the glass covered streets. The boy was holding a small package wrapped in brown paper under his arm. He stopped in front of the Silbermann house, got off his bike, and walked up to the front porch.

Frederick must have ordered something, thought Zammie.

“Are you Zammie Pineda?” asked the boy.

Zammie was stunned for a moment. “Yes.”

“This is for you.”

|

| German boy and bicycle, 1938 |

The boy handed the small package to Zammie. He turned around and began walking back to his bicycle when Zammie called out to him.

“Who is this from? And how did you know I’d be here?”

The boy got on his bike. “The old Indian man sent it to you. He told me you’d be here.” The boy then peddled back from whence he came.

The old Indian man?

Zammie knew what this was. He ripped open the brown wrapper and lifted the lid on the small box. Inside was what he was expecting. It was a small Arjuna statue. It was the same size as the one they saw in the taxi cab in Paris and roughly half as big as the one he had at home.

This must have meant it was time for them to leave.

When Kyla and Zammie woke up they were back in Zammie’s room. They had first activated the Arjuna at roughly three o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and when Zammie looked at the clock again it read “3:06”.

Wow! thought Zammie. “Only a five minute nap!” he said to Kyla.

The two cousins had said their goodbyes to Susan and Marga and the rest of the Silbermann family. Then they went around to the rear of the blackened synagogue, sat down on the ground, and pressed down the six arms of the mini-Arjuna. It began whirring and spinning and within seconds its little red eyes put the two children into a deep sleep. The next thing they knew they were back home.

“I felt really bad for that family,” said Kyla. “That wasn’t fun like the other trips.”

“History isn’t always fun,” said Zammie. “Sometimes it’s just . . . eye-opening.”

“Eye-opening? That was awful, Zammie. Was there nothing we could have done for those people?”

“No. I don’t think we can change history. It’s already happened.”

“Then why do you think the Arjuna would send us to a sad place like that?”

Zammie thought for a second. “To learn? To be careful of what's going on around us? So maybe in the future people won’t make the same mistakes. Maybe if they knew a little more, people would think twice before destroying someone else’s home or business. I’m not sure. It’s hard to understand how that much hatred even starts.”

“That means we need to start telling our friends what we’ve seen.”

“Yeah. But we can’t say we travel back in time, Kyla. They’ll think we’re crazy.”

“That’s true,” said Kyla. She stood up. “I’m gonna go home now. I wanna see my mom.”

“Okay. I’ll stop by later.”

“Alright.” Kyla walked out of the room.

Zammie lay back down on the bed and reflected on what he experienced: the shock of Herschel shooting that man, the terror of the riots, and the strength of the Silbermann family working together to rebuild what was destroyed. Sometimes these history lessons almost seemed too fantastic to be true. Could all of that have really happened?

When Zammie sat back up he noticed a card sitting next to the Arjuna on his desk. He walked over and picked it up and realized it was Herschel’s postcard written to his parents. Zammie hadn’t been able to return it to Herschel. The note on the back was written in German so Zammie didn’t understand it, but it read:

"With God's help.

My dear parents, I could not do otherwise, may God forgive me, the heart bleeds when I hear of your tragedy and that of the 12,000 Jews. I must protest so that the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do. Forgive me.”

Zammie would ask his mother to take him to the post office and figure out how to have it mailed. It would be arriving at its destination late, but the message contained would be as powerful as ever.

THE END

The above excerpt was from the novel

KILLING FOR COUNTRY

by Jason McKenney

THE JOURNEY TO ANCIENT GREECE

A RIDE ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

WITNESS TO THE FIRST THANKSGIVING

The inside of the house was a blend of traditional German and Jewish influence. The wooden fixtures, clocks, and architecture were of classic German design and engineering. There was also a silver decorative case containing a mezuzah attached to the front doorframe (the case held a piece of parchment upon which select verses from the Torah were written). A quilted tapestry hung on the wall with twelve squares representing the twelve original tribes of Israel, and Zammie noticed a couple small wooden statues on the book shelves that looked like dancing Rabbis.

The inside of the house was a blend of traditional German and Jewish influence. The wooden fixtures, clocks, and architecture were of classic German design and engineering. There was also a silver decorative case containing a mezuzah attached to the front doorframe (the case held a piece of parchment upon which select verses from the Torah were written). A quilted tapestry hung on the wall with twelve squares representing the twelve original tribes of Israel, and Zammie noticed a couple small wooden statues on the book shelves that looked like dancing Rabbis.

The rioters destroyed more than 260 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many of the synagogues burned throughout the night. Local firefighters had been told to stand down and to only intervene to keep flames from spreading to non-Jewish buildings. According to some estimates, the gangs of Nazi storm troopers had destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish businesses, set fire to more than 900 synagogues, while killing 91 Jews and arresting and deporting roughly 30,000 Jewish men to various concentration camps.

The rioters destroyed more than 260 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many of the synagogues burned throughout the night. Local firefighters had been told to stand down and to only intervene to keep flames from spreading to non-Jewish buildings. According to some estimates, the gangs of Nazi storm troopers had destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish businesses, set fire to more than 900 synagogues, while killing 91 Jews and arresting and deporting roughly 30,000 Jewish men to various concentration camps.

The inside of the house was a blend of traditional German and Jewish influence. The wooden fixtures, clocks, and architecture were of classic German design and engineering. There was also a silver decorative case containing a mezuzah attached to the front doorframe (the case held a piece of parchment upon which select verses from the Torah were written). A quilted tapestry hung on the wall with twelve squares representing the twelve original tribes of Israel, and Zammie noticed a couple small wooden statues on the book shelves that looked like dancing Rabbis.

The inside of the house was a blend of traditional German and Jewish influence. The wooden fixtures, clocks, and architecture were of classic German design and engineering. There was also a silver decorative case containing a mezuzah attached to the front doorframe (the case held a piece of parchment upon which select verses from the Torah were written). A quilted tapestry hung on the wall with twelve squares representing the twelve original tribes of Israel, and Zammie noticed a couple small wooden statues on the book shelves that looked like dancing Rabbis.

The rioters destroyed more than 260 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many of the synagogues burned throughout the night. Local firefighters had been told to stand down and to only intervene to keep flames from spreading to non-Jewish buildings. According to some estimates, the gangs of Nazi storm troopers had destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish businesses, set fire to more than 900 synagogues, while killing 91 Jews and arresting and deporting roughly 30,000 Jewish men to various concentration camps.

The rioters destroyed more than 260 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Many of the synagogues burned throughout the night. Local firefighters had been told to stand down and to only intervene to keep flames from spreading to non-Jewish buildings. According to some estimates, the gangs of Nazi storm troopers had destroyed more than 7,000 Jewish businesses, set fire to more than 900 synagogues, while killing 91 Jews and arresting and deporting roughly 30,000 Jewish men to various concentration camps.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for submitting a comment. We will review and post your comment as soon as possible.