PART 1

September 1936

Ding ding! Another streetcar bell signaled its impending departure. 7AM was the height of rush hour and the clog of workers scurrying about to catch a ride from Quievran, Belgium, across the border into

Ding ding! Another streetcar bell signaled its impending departure. 7AM was the height of rush hour and the clog of workers scurrying about to catch a ride from Quievran, Belgium, across the border into

Since the end of World War I in 1918, much of Western Europe had been in both economic and political flux. Germany had received most of the punishments handed out by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 including military limitations, monetary payments to their neighbors, and the surrendering of some land to France

|

| Herschel Grynszpan |

Ding ding! There went another car. He would have to jump on one of these cars soon if he expected to cross the border without having his papers checked. During the slower traffic periods the crossing guards would check the permits of people crossing into France

Ding ding! Herschel carried a small knapsack at his side. He pulled up the collar on his brown wool coat in an attempt to hide his youthful face in hopes of looking older. He pulled the bill of his dark gray Jeff cap down over his eyes and made his way towards one of the streetcars. When he reached the door of the car an attendant with a thin, black mustache and wearing a blue uniform stepped in front of him. He asked Herschel something in French. Herschel didn’t understand him but he assumed the attendant was asking for payment. Herschel dug in his pocket for coins and gave the attendant a single franc. Herschel must have guessed correctly because the attendant gave Herschel a ticket, some change, and allowed him onboard.

Even at this early hour the car already smelled of sweat and cigarette smoke. Herschel found an open seat and sat down. A couple more men boarded the car before it lurched into motion and began rolling the short distance to the station in Valenciennes

Herschel kept his eyes on the crossing guards as the car approached the border checkpoint. The car slowed to a stop and one of the guards walked up to the driver. The guard was wearing a well-pressed navy uniform with a captain’s hat covering his brown hair. He had a quick discussion with the driver, and the driver pointed to the back of the trolley right at Herschel. Herschel’s heart jumped up his throat.

The guard made his way down the narrow aisle. The Belgian workers did their best to make way for him to pass. He approached Herschel and said something in French. Herschel didn’t understand French, but even if he had he probably wouldn’t have been able to speak. His mouth had gone completely dry.

Herschel looked up at the guard, but before he could make any other response the man sitting next to Herschel replied first. He said something with a “monsieur” at the end of it. The man reached in his pocket and handed the guard a billfold with an identification card. The guard looked it over and handed the billfold back to the man. Then he returned to the front of the car and exited.

Herschel’s entire body sighed in relief. The driver must have been pointing to the man sitting next to him. Apparently the driver wasn’t positive that man had a worker’s permit. That was a close one.

Soon the trolley reached the station in the larger town of Valenciennes Paris

But more importantly he wanted to find a way to help his parents who were still in Germany

November 1938

Abraham Grynszpan was in his late forties and the daily grind of a plumber’s life was beginning to wear down his body. His back ached, his knees were sore, and the arthritis in his thick fingers grew more painful by the week.

|

| Holishkes |

|

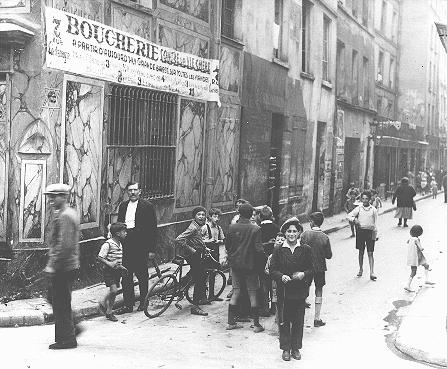

| Image of the Jewish quarter of Paris pre WWII |

“Evening officers,” he said. There were two Parisian policemen in dark blue uniforms standing on the porch of his small house.

“Evening, Mister Grynszpan. Is Herschel at home?”

“No, I told you before. He has left. We have not seen him for weeks.”

“I know you’ve told us that before, Mister Grynszpan, but we have received reports of a teenage boy entering and leaving your house late at night.”

“From who?” asked Abraham. “Who’s telling you these stories?”

“May we come inside, Mister Grynszpan?”

“Now? But I am just sitting down for supper.”

“I am truly sorry, Mister Grynszpan. It won’t take but a moment.”

“Tomorrow,” said Abraham. “Come back tomorrow—“

The second of the two officers, the much larger one, stepped up to Abraham, towering over him, and pushed the door open. He brushed past Abraham and entered the house.

The second of the two officers, the much larger one, stepped up to Abraham, towering over him, and pushed the door open. He brushed past Abraham and entered the house.

“What are you doing?” asked Abraham. “You have no right!” He did his best to feign indignation, but they all knew he was guilty of harboring a fugitive.

“This will just take a moment, Mister Grynszpan,” repeated the first officer.

The larger officer stomped through the tiny house, opening doors and ruffling through closets. After several minutes of searching and researching the domicile the large officer finally gave up.

“I told you he’s not here,” said Abraham. His heart was pounding and he tried to hide the shaking in his hands. If only these officers knew exactly how close they were.

“So you say. When he returns I want you to call us, is that understood, Mister Grynszpan? What you are doing is illegal, and you’ve worked too hard here in Paris

The officer looked at Chawa, smiled and nodded. “Madam.” Then he turned and walked out of the house with the larger officer following closely behind.

Abraham closed the door with his trembling hands. “Wine. Please.”

Chawa brought him a glass of red wine and he drank it down in one gulp.

“Animals,” she said. “Barging into our home like that.”

“They’re just doing their job, Chawa.”

“Their job is to interrupt your supper and search through my closet--?”

She stopped when she heard the steps behind her. They both looked over to see their teenage nephew Herschel, now seventeen years old, creeping towards the front window to see if the police were gone. He had grown a couple inches since arriving in France

Herschel knew this day would come at some point, but he was still taken by surprise to actually hear his uncle say the words.

“But Abe, where will he go?” asked Chawa.

“I don’t know, but this has gone on long enough. They will not give you citizenship here, Herschel. You must go to Poland

“But I can’t, Uncle!”

“You have to figure out a way! If you stay here you will have us all go to jail! The police are watching me wherever I go now! They are watching your aunt wherever she goes! Is this what you want?”

“Of course not—“

“I have paid your expenses for two years! I have paid your police fines. What else do you expect from me? Have I not been more than fair? Tell me?”

“Please, Uncle! I just need a little more time!” said Herschel. He was mature beyond his years, but the thought of being turned out on the street still frightened him. “Give me one more week. If I haven’t heard from the Consulate by then, then I will go. I promise.”

“You’ve been promising for months! Not anymore! You leave tonight!”

“But Uncle…”

“No more argument! You haven’t achieved anything. You can’t even get into school, Herschel. You’re wasting your life here!”

Herschel was stung. “Wasting my life? What about my parents? What about your brother?”

“Eh? What about them? They are in Poland

“But they’re not legal their! You know this, Uncle! Auntie, will you explain to him—“

“Aye! Don’t bring her into this!” said Abraham. “We’ve had this conversation a thousand times. There’s nothing more we can do for you, Herschel. You found a way to sneak into France

Herschel looked at his aunt with scared eyes. “Auntie?”

“I said don’t talk to your Aunt,” said Abraham. “This is my decision.”

Plans on where to go and what to do quickly ran through Herschel’s mind. Maybe he could find a hotel for the night. Maybe he could sneak across the border back into

Since arriving in Paris

He just didn’t expect that day to be this one.

* * *

Twelve-year-old Zammie was staring at the newspaper he had found on the table in the café . The wording was in French which he couldn’t read, but both he and his younger cousin Kyla could speak and understand the French people around them with no problem. This reading issue was still an enigma they had to figure out while on these time journeys they took.

Twelve-year-old Zammie was staring at the newspaper he had found on the table in the café . The wording was in French which he couldn’t read, but both he and his younger cousin Kyla could speak and understand the French people around them with no problem. This reading issue was still an enigma they had to figure out while on these time journeys they took.

“November six. Nineteen thirty eight,” said Zammie. Making out the date on the paper was simple.

“What happens in 1938?” asked Kyla.

“In Paris

“Here is your sandwich, Monsieur Zammie.” A cheerful waiter placed a sliced baguette filled with dark forest ham, goat cheese, and a sweet, creamy butter spread on the small table in front of Zammie. “And yours, Mademoiselle Kyla.” She was given a soft croissant stuffed with ham and melted Swiss cheese. Both children had also ordered freshly squeezed lemonades to drink. The eyes of the two cousins lit up. Thankfully they always arrived at these historical destinations with adequate amounts of the local currency because more often than not they also arrived with empty bellies.

|

| Woman wearing a snood. |

“Are we in America

“I don’t think so,” answered Zammie. “The signs aren't in English. And those buildings look like the ones from the European section at Epcot Center

|

| Art deco architecture |

The two cousins had found a newspaper left on a small round table at one of the sidewalk cafés. They poured through it in hopes of gleaning any other contextual clues about their surroundings when they decided to stay at the café and order supper.

It was nearly nine in the evening when Zammie noticed a teenage boy with thick, dark hair and a sad countenance walk down the sidewalk and sit at the table next to them. The waiter walked over to the boy and said something to him in French. The boy looked at the menu that was sitting on the table and pointed at one of the items. The waiter must not have been asking for his order yet because he said “No, monsieur,” and then repeated his statement.

Kyla noticed that Zammie was staring at the exchange taking place at the other table.

“What’s going on?” she asked Zammie.

“I don’t think that boy understands French,” he said. “Do you not speak French?” Zammie asked the boy.

Both the boy and the waiter looked at Zammie. The waiter had a look of amazement on his face.

“No,” said the boy. “What is he asking me?”

“He doesn’t want you to sit there because that table is reserved for one of the owner’s friends for some reason. I guess it’s his lucky table.”

“Oh.” The boy immediately began to rise.

“Thank you, Monsieur Zammie,” said the cheerful waiter.

“What language does that boy speak?” asked Kyla.

“I don’t know. It all sounds English to me.”

The boy began to walk to another table when Zammie addressed him again. “You can sit with us if you want.”

“It’s alright. I don’t want to bother you.”

“It’s no bother. And I can translate for you to the waiter.”

The boy paused for a second then nodded without smiling and took a seat next to Zammie at their small table.

“Thank you,” he said.

“Sure,” said Zammie.

To Zammie’s ears he was speaking English to both the boy and to the waiter, but to their ears he was speaking French to the waiter and German to the teenage boy. The waiter was impressed to hear a boy of Zammie’s age speak both languages so fluently since they have so few common roots.

Zammie ordered a bowl of soup and a sandwich for the teenager with a cup of coffee to drink. Naturally, this ability to freely communicate in any language on their travels made these trips much more enjoyable.

“What language do you speak?” Kyla asked the boy. It was an awkward question but she wasn’t sure how else to ask it.

“German, of course. And some Yiddish,” he answered.

“What’s Yiddish?” asked Kyla.

“A Jewish language.”

“My name is Zammie.” He held out his hand towards the boy. The boy shook it.

“Herschel,” he said. “Herschel Grynszpan.”

“My name is Kyla.” Kyla shook hands with Herschel as well.

“Why would you want to live in Paris

“It’s not for lack of trying, believe me,” said Herschel. “But I have nowhere else to go. The French government has denied my request to stay in France , but I have no re-entry permit for Germany

“Where are your parents?” asked Kyla.

Herschel’s head dropped for a second in thought. “They are in Poland

“A what?” asked Zammie.

|

| Jews being deported from Germany to Zbaszyn. |

“What?” Kyla was shocked.

|

| Jewish children deported from Germany in Dec. 1938 |

“That’s awful,” said Kyla. She was genuinely stunned at the thought of a government forcing out its own law-abiding citizens.

“How did you get to Paris

“My parents sent me to live with family in Belgium Germany Hannover , and they hoped I could create a future for myself elsewhere. But I couldn’t stay in Brussels so I snuck across the border into France Paris

“The French government can’t help?” asked Zammie.

Herschel almost started laughing. “Oh, please. The French government? They couldn’t care less about German Jews. Especially those who had been deported to Poland

“There has to be something you can do,” said Kyla.

“Like what? Maybe go to the German Embassy? Tell them how poorly the Jews are being treated in their country right now?”

“Would that work?” asked Zammie.

Herschel frowned. “Maybe. Doubtful. But what about you two? What’s your story?”

|

| Rounded up: Deported to Poland |

“Tourists?” Herschel had a wide grin on his face. “But you’re just kids. So where is your family?”

“California

“America

“Yep.”

“You don’t look American.”

Now Zammie almost laughed. “What does an American look like?”

“Well . . . I dunno . . . you look . . .”

“Our parents are from the Philippines , but we were born in California

“Philippines America

“Your order, monsieur.” The waiter arrived with the plate of food and a small cup of coffee for Herschel. Zammie wasn’t a coffee fan, but that dark roast smelled pretty good.

Herschel scarfed down the sandwich and drank the soup quickly and stood up to leave. “It was a pleasure meeting you two,” he said, “but I really must be going now.”

“It was nice meeting you, too, Herschel,” said Kyla. “I hope things work out for your family.”

Herschel took one step from the table and stopped. He turned back to the two cousins. “Where will you stay tonight?”

Kyla and Zammie looked at each other.

“I don’t know,” said Zammie. “I hadn’t really thought about it.”

“It’s late,” said Herschel, “and kids shouldn’t be out on these streets alone after dark. You’re welcome to stay with me if you like.”

“Your uncle won’t mind?” asked Zammie.

Herschel’s mood darkened. “I don’t stay with him anymore. I have a room at the Waning Crescent

“Good idea,” said Kyla.

“Okay,” said Zammie. “Lead the way, Herschel.”

Herschel left a few francs on the table and led the two cousins down the still-busy Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin.

In August of 1938 the German government, led by Chancellor Adolph Hitler, announced that all current residence permits for all foreigners were being cancelled and new ones would need to be applied for. Through this tactic, the Nazi officials would be able to deny all new permits to Jewish foreigners in Germany in hopes of eventually forcing them to be deported from the country. Poland, however, said that it would not accept Jews of Polish origin being deported from Germany because at the end of October, the Polish government would no longer consider those people to be Polish citizens. In order to beat this deadline, on October 26th the Gestapo secret police was ordered to arrest and deport all Polish Jews from Germany as quickly as possible.

The Grynszpans were among the estimated 12,000 Polish Jews arrested, stripped of their property and herded aboard cargo trains headed for the Polish border. Upon arrival they were taken off the trains and forced to walk nearly a mile to the Polish border town of Zbąszyń. Still, Poland refused to admit them any further. The Grynszpans and thousands of other deportees were left stranded along the border while being fed by the Polish Red Cross. It was from Zbąszyn that Herschel’s mother Berta sent a letter to her son in Paris. It was the agony and helplessness spurred on by the letter that many believe was the final push for Herschel towards the tragic actions he was soon to commit.

The cafés were jammed with customers that night. The rippling of a thousand conversations and the clanking of silverware filled the air as the three young pedestrians did their own dodging in and out of traffic along the Parisian streets.

In August of 1938 the German government, led by Chancellor Adolph Hitler, announced that all current residence permits for all foreigners were being cancelled and new ones would need to be applied for. Through this tactic, the Nazi officials would be able to deny all new permits to Jewish foreigners in Germany in hopes of eventually forcing them to be deported from the country. Poland, however, said that it would not accept Jews of Polish origin being deported from Germany because at the end of October, the Polish government would no longer consider those people to be Polish citizens. In order to beat this deadline, on October 26th the Gestapo secret police was ordered to arrest and deport all Polish Jews from Germany as quickly as possible.

The cafés were jammed with customers that night. The rippling of a thousand conversations and the clanking of silverware filled the air as the three young pedestrians did their own dodging in and out of traffic along the Parisian streets.

“Have you seen the Eiffel Tower

“No.”

“What about the Arc de Triomphe?”

“What’s that?”

“What’s that?! Oy vey! You go sightseeing in Paris

“Oy vey. It’s an old Yiddish expression,” said Herschel. “It means ‘you gotta be kidding me!’”

He led the cousins off the sidewalk and towards one of the tall, gray buildings that lined the street. They entered into an open doorway with a peach and cream-colored awning overtop of it. The lobby of the hotel was a small room with red walls and low mood lighting. There were two pretty women sitting on a sofa smoking long cigarettes on the far side of the lobby. They were wearing short, black dresses and had very red lips. One of them smiled at Zammie. He grinned and turned around embarrassed.

Herschel paid the attendant and he led the cousins upstairs to the second floor. Their room was modest in size and smelled like perfume and mothballs. There was one bed, one small cot, and one set of wooden drawers.

“Where’s the bathroom?” asked Kyla.

“At the end of the hall,” said Herschel. “You two can have the bed. I’ll take the cot.”

“No, we can sleep on the floor,” said Kyla. “It wouldn’t be the first time.”

“Forget it. I have to get up early anyway. I’ll probably be gone when you wake up.”

“Where are you going?” asked Zammie.

“Nosy,” said Kyla.

“I’m just asking,” said Zammie.

“It’s alright,” said Herschel. “I’ve been thinking about what we were saying earlier. I think I’ll try the Embassy tomorrow.”

“Really?” asked Zammie. “You think they can help?”

“It won’t hurt to try,” said Herschel.

Zammie noticed that there was something weighing heavily on Herschel’s thoughts. For brief moments he would lighten up and smile and joke like a normal boy of his age, but then he would quickly sink back down to a very serious and sullen place in his mind, as if he had a complicated puzzle that he was trying to figure out but wasn’t giving him any enjoyment.

Herschel sat down on the cot and pulled out a pen. He began scribbling a note on the back of a postcard. Zammie sat down on the rickety twin-size, and Kyla left to go to the bathroom.

“Herschel?”

“Yes.”

“Would you mind if we go to the Embassy with you tomorrow?”

“Yes, I would mind. You cannot go with me.”

“Are you sure? It might help to have support.”

“No, Zammie. I have to do this alone.”

“Okay. If you say so.”

Zammie lay back on the bed and stared up at the circular brown water-stains on the ceiling. He was trying to figure out what they were doing in Paris

“That bathroom is dirty.” Kyla had entered back into the room. “And it smells like rotten milk.”

No one responded to her.

“What are you writing, Herschel?”

“Just a letter.” He finished writing and put the postcard and pen on the floor next to his cot.

“To who?” asked Kyla.

“Nosy,” said Zammie.

“Funny. I can’t help it. I’m just curious.”

“It’s to my parents,” said Herschel.

“You miss them?” asked Kyla.

“Of course.”

“Well, I hope you can get back to them soon.”

Herschel gave a weak smile, but didn’t say anything.

All three children had experienced a very eventful day and it wasn’t long until the two cousins were deep asleep. Herschel, on the other hand, had trouble falling asleep. His mind was restless with feelings of anger and resentment; resentment towards his uncle and towards the French government, but most of all towards the Nazi party in his home nation. The thought of his parents being shipped off to live in horse stables made him as angry as anything had ever made him in his short life. Even the Polish government wouldn’t accept them. What on earth was happening to Europe now? Why the divisiveness? Why were people allowing themselves to be pitted against one another so easily?

Eventually Herschel would slide off into a fitful sleep. He awoke before dawn and carefully put on his coat and flat cap, and snuck out of the room without disturbing the two cousins.

TIME TRIP ADVENTURE 4

KILLING FOR COUNTRY

Available at Amazon.com!

TIME TRIP ADVENTURE 2

A RIDE ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

TIME TRIP ADVENTURE 3

WITNESS TO THE FIRST THANKSGIVING

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for submitting a comment. We will review and post your comment as soon as possible.